Recent political elections, such as the upcoming presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, have exacerbated tensions at the border. Bills such as the most recent Texas Senate Bill 4 target Hispanic populations by permitting officers to arrest people they suspect of being in the country illegally and deport migrants to Mexico. As 94% of the Valley is Hispanic or Latinx, this bill could lead to racial profiling and wrongful arrests.

Beyond immigration narratives, why is it important to show a diverse range of stories about the Valley?

JA: Chicano literature was originally about the immigrant experience. They’re wonderful stories that are evocative of the life of my own parents because they were migrant farmworkers. But it wasn’t my experience.

Maybe the hardest thing is to convey to people who are not from the Valley what it’s like to live there without going into stereotypes. I’m also very interested in looking at some of the problems in the Valley, for example, gay culture here. Drag shows are a lot more open, but there’s still a lot of resistance.

Another problem is the way the Valley is growing. There’s a lot more people, even something as stupid as Elon Musk and Starbase. There are a lot of new influences changing the Valley in interesting ways.

Since bringing SpaceX to Brownsville’s Boca Chica Beach in 2014, Elon Musk named the area “Starbase” and uses the space to manufacture and launch Starship rockets. Negative impacts from the launches, such as debris, endangerment to local wildlife, and rising housing costs, have led organizations across the Valley to protest against SpaceX’s presence in the city.

Your work blends science fiction elements with your Mexican-American background. How did you steer away from stereotypical portrayals of Mexican-Americans and write something true to your experiences?

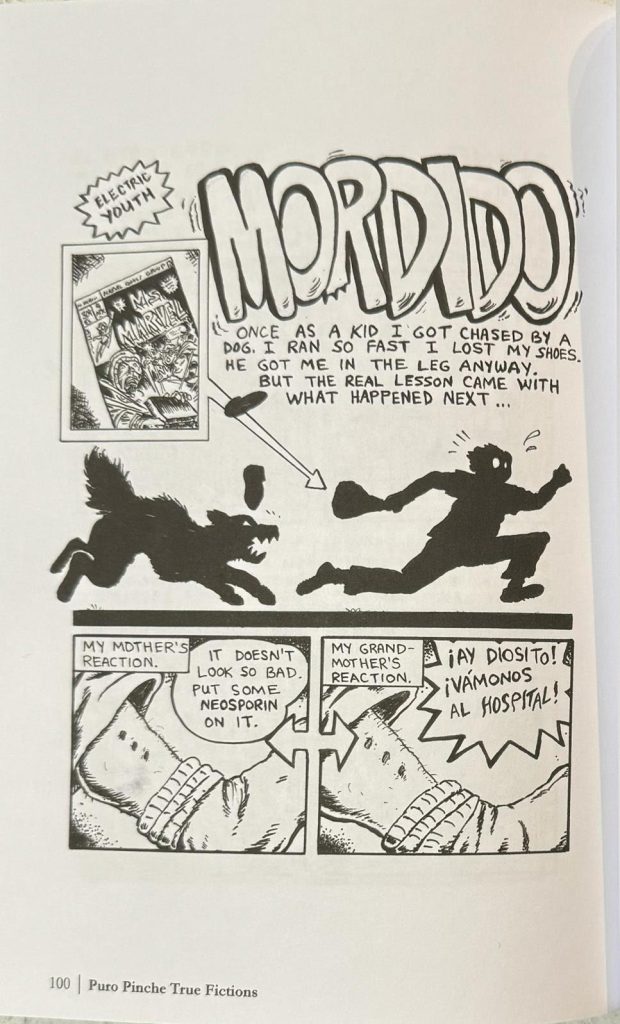

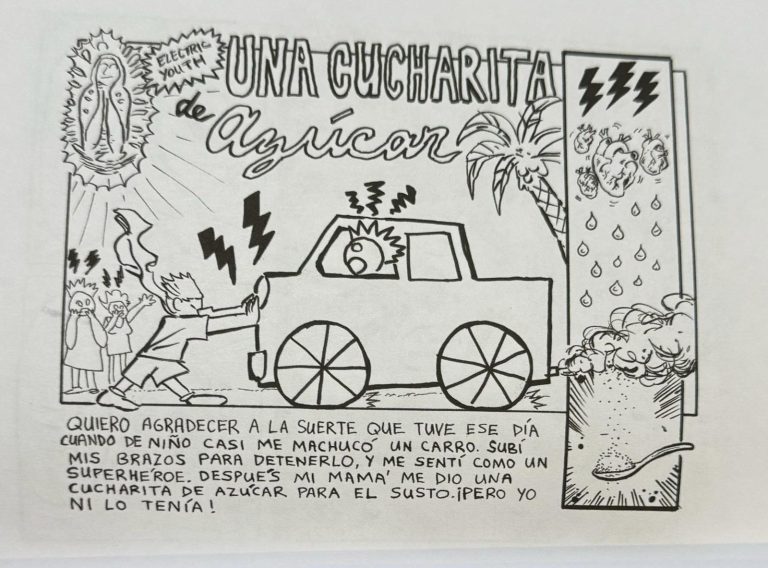

JA: I’m a second-generation Chicano, and my mother is from Mexico. I grew up with a pretty standard 1970s childhood. Even though we would cross the border to Reynosa and grew up speaking Spanish, I’m also very assimilated. I love science fiction, Star Trek and Star Wars. My work is a mixture of all that.

The short story Genoveva is a lot of what I recorded my grandfather saying. I often don’t translate it because it didn’t feel right. It’s a way to respect him to leave it the way it was.

“Genoveva” snapshots a grandfather’s stern personality, one where he tells life stories for the narrator to learn from. Alaniz said he used his own grandfather as inspiration.

With only 7% of authors and writers in the U.S. being Hispanic or Latinx, it’s important to highlight those who can accurately write about their culture. How did you decide not to change your writing in Spanglish to fit into the publishing industry?

I think things have really changed a lot because I wrote a lot of this stuff a long time ago, in fact, even when I was still at UT Austin, and I held on to it. In the last couple of years, you’ve had a lot more smaller presses owned by Mexican-Americans that are open to Chicano literature and comics. FlowerSong Press is based in McAllen, and they were totally open to this material because they’re from the Valley.

They understood the value of this and how it gathers people that would read it. Part of it was having patience and waiting for the landscape to change. I was at a publisher that was very comfortable with using Spanglish and saw the value in it.