The San Juan Hotel: Why Historic Preservation is Necessary for Accurate Storytelling, Consciousness & Reconciliation

Story by Dr. Stephanie Alvarez (ella/her)

Edited by Abigail Vela

Trigger Warning: This historical article contains information that depicts torture, death, and violence. Please read with caution.

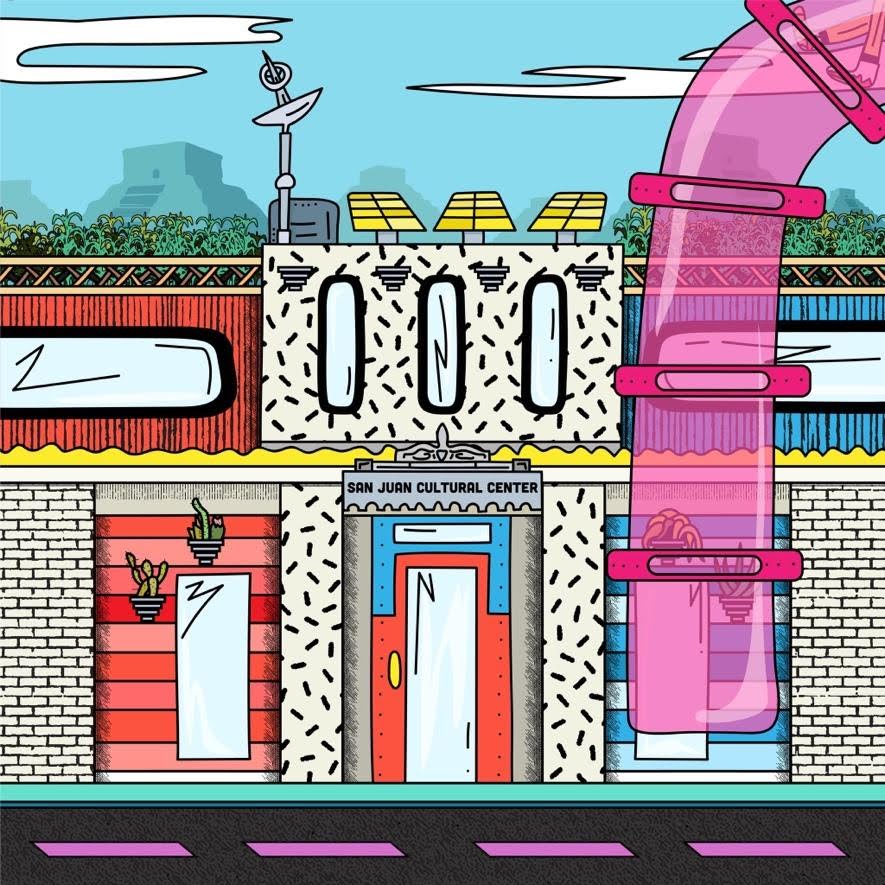

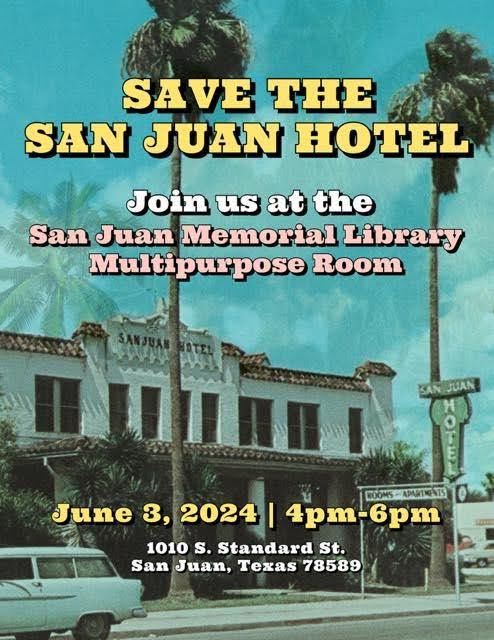

The city of San Juan, Texas, purchased the San Juan Hotel, a registered Texas Historical Landmark, in November 2023 as part of its downtown revitalization plan. In February 2024, the City of San Juan City Commission unanimously voted to demolish the San Juan Hotel to build an event center.

Upon learning of the plans to demolish the San Juan Hotel, residents in San Juan and throughout the Río Grande Valley mobilized to form the Save the San Juan Hotel Initiative to stop the demolition of the hotel in collaboration with the Hidalgo County Historical Commission and support from La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE) and Proyecto Azteca.

Since May 2024, community members have launched an online petition, held meetings and repeatedly attended bi-weekly city commission meetings requesting a workshop or meeting so that we may share our perspective in the hopes of convincing the City of San Juan officials not to demolish the San Juan hotel, but instead preserve the hotel and convert it into a site of consciousness and reconciliation.

Brief History of the San Juan Hotel: Site of White Settler Colonialism, State-Sanctioned Violence and Segregation

The original San Juan Hotel was built in 1919, a year before the founding of the City of San Juan, approximately one block south of its current location. By 1920, the San Juan Hotel was newly constructed at its current location, where it remains today. The hotel sits on the south side of the railroad tracks on Old Business 83 between Nebraska Ave and Veterans Ave.

The physical location of the San Juan Hotel is of great significance because it is symbolic of the racial segregation of both San Juan and the Río Grande Valley. The railroad tracks literally divided the White and Mexican populations, with the White residents living on the south side and Mexican Americans living on the north side of the tracks. To be clear, this division was deliberate and enforced, most often through violence, by law enforcement. Elders in the city of San Juan and other parts of the Valley detail how going to the south side of the train tracks was dangerous and, at times, deadly, especially after dark.

Long-time residents such as Arturo Guajardo describe how even until the early 1970s, not only was the city segregated, but that on the north side of town, there was no indoor plumbing and that the sewage from the White neighborhood was dumped into the Mexican side of town. There were Mexican schools and White schools, Mexican stores and White stores, Mexican eateries and White eateries. The San Juan Hotel is not only symbolic of this segregation, but it is also a site that represents White settler colonialism throughout the Río Grande Valley. Its location along the railroad tracks is no coincidence.

One of the primary purposes of the San Juan Hotel was to host land parties for White Northeasters and Midwesterners who came to the mythical “Magical Río Grande Valley,” promoted by folks like John Shary and John Closner, looking to make their fortune in agriculture with the promise of fertile land, warm climate, irrigation, cheap and docile Mexican labor, and a tropical paradise. These were known as “land parties” organized by colonizers like Shary and Closner. The San Juan Hotel hosted many such people in search of paradise.

What was the promise of fortune for White settlers meant violence, terror, oppression, suffering, and often death for Mexican Americans through both legal and extralegal means. The hotel was built at the height of what historians call La Matanza/The Slaughter and La Hora de Sangre/The Time of Bloodshed; 1910-1920. This period marks an escalation of state-sanctioned violence against Mexican and Mexican Americans, during which it is estimated that thousands of Mexicans were lynched by vigilantes, local law enforcement, and, in particular, the Texas Rangers, referred to in Spanish as los rinches.

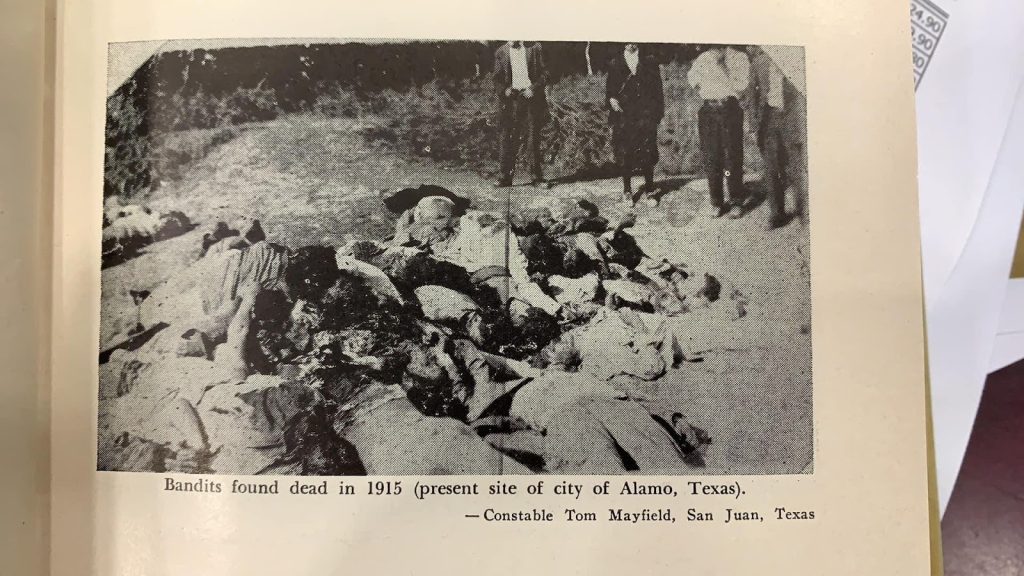

The role of the Texas Rangers was critical to the success of White settler colonialism in the Río Grande Valley. Their main purpose was to protect the land of the White settlers, which the settlers most often stole or obtained illegally or unethically from Mexican Americans. In addition, this period coincides with what is frequently referred to as the “Bandit Wars.” While there was certainly an influx of migrants from Mexico due to the Mexican Revolution and some raids carried out by Mexican revolutionaries, the majority of the Matanza was carried out by Rangers against innocent Mexicans. Scholars such as Trinidad González prefer using the term Sediciosos over Bandits as the term Sedicionists better describes their agency and motives. Regardless of the term, most can agree that what it boils down to was a Race War.

The extralegal violence and executions, however, went beyond 1920 as former Texas Rangers like Mayfield then became constables & deputies. The use of the hotel as a site of lynchings makes sense both during La Matanza and into the 1970s as it was and is a physical reminder of what was to happen if a Mexican were to cross the tracks.

Repeatedly, when asked, “What do you know about the San Juan Hotel?” local elders respond, “Ahí colgaban a los Mexicanos.” Tom Mayfield is often identified as the perpetrator of those lynchings.

Tom Mayfield—El Ronco

While honored as a hero by some, most Mexican Americans in the region recall him as an evil man who ruthlessly killed Mexican Americans as a Texas Ranger, Constable, Marshall and Deputy Sherriff of Hidalgo County. Referred to as El Ronco for his raspy voice by locals, Tom Mayfield was not only a Ranger during La Matanza, but he was the law in San Juan, Pharr, and Alamo from 1910 to 1921 and again from 1938 to 1963 when Erasmo Bravo, the first Mexican American constable of the region, defeated him.

There are countless stories regarding his terror, murders, and horrific brutality. One long-time San Juan resident recounted that Mayfield was always able to get a quick confession out of Mexicans because he would pull their nails with plyers. Other residents tell of how Mayfield was known to carry a whip and how he would brutally whip any Mexican found on the south side of town. One atrocity often attributed to Mayfield is the mass lynching of Mexicans in Alamo, Texas. Some say the number is 13, and others say up to 30. What we know for sure is that while Mayfield denies being the culprit, he kept a photo of the lynching, provided at least one person with a copy of the photo, spoke about it often, and was the primary Ranger for the area at the time making him responsible for investigating the deaths, which he never did, making him at the very least, complicit in the lynching.

Not only are the lynchings at the San Juan Hotel attributed to Mayfield, but he resided at the San Juan Hotel after losing to Bravo. The City of San Juan paid his rent as part of his retirement benefits. Those who visited him recall that he proudly displayed his “trophies,” memorabilia from his victims, on his dresser at the San Juan Hotel, where he spent the last of his years living until his death in 1966. Additionally, the Bank of San Juan proudly displayed his arsenal of weapons for years. One resident recounted how he refused to do business at that bank because of that display.

While the residents of San Juan remember Mayfield for the terror he inflicted, he has been memorialized as a hero in multiple ways. For decades, the City of San Juan’s ballpark on Ridge Road and San Antonio Ave was named Mayfield Park.

However, in 2016, I taught a Mexican American Studies course at UTRGV on muralism and oral history in the City of San Juan, which resulted in the mural “Movimiento Sin Fronteras” by Corina Alvarado and Iliana Rodríguez. It was during this course that we learned the true history of Mayfield, as told by the residents of San Juan. Upon learning this history, UTRGV students and community members, including myself, asked the city to rename the ballpark, given the horrific and largely undocumented history of Mayfield.

In 2017, the park’s name was officially changed to San Juan Sports Complex, although one of the two fields still carries his name. The other is named after Lalo Arcaute, the City of San Juan’s first Mexican American Mayor. Nevertheless, Mayfield was honored with a historical marker in 1993 outside the San Juan Hotel for his long career in law enforcement and, as the marker reads, “earning the community’s highest respect.”

Possibility for Consciousness and Reconciliation

Since May of 2024, the community has been organizing against the demolition of the San Juan Hotel as part of the city’s downtown revitalization plan.

The Save the San Juan initiative has asked the city to take immediate steps to preserve the hotel and even offered, along with Proyecto Azteca, to board up the windows and doors, install a tarp on the ceiling, mow the lawn, and paint the building. We have also requested that the city reinstate its historic preservation committee, which has been inactive for years despite the fact that the city’s charter calls for one.

Brian Godinez of ERO Architects was contracted to develop a downtown revitalization plan that would cost well over ten million dollars and sustains that the hotel is not salvageable. Nevertheless, we have repeatedly requested that an independent historical preservation organization evaluate the feasibility of restoring the hotel. ERO does not specialize in historic preservation, and community members like Mae Anzaldúa heed that ERO’s work at the Hidalgo County Court House should be an example of why the city should not work with ERO.

Gabriel Ozuna of the Hidalgo County Historical Commission has repeatedly attended city council meetings attesting to the value of historic preservation, and his expertise has fallen on deaf ears. In June of 2024, Preservation Texas listed the San Juan Hotel as one of the most endangered places in Texas. Ozuna, soon after, presented the city commission with a proposal from Post Oak Preservation Solutions to develop a preservation plan that includes a structural assessment, maintenance plan, and possible funding sources for less than $7,000—some $30,000 less than ERO’s services.

In addition, we have repeatedly presented the city with grants they may apply for and have offered our services, free of charge, to apply for some of them. Above all, we have requested a workshop and/or meeting with the City Commission for eight months to discuss this matter in detail. After all, while ERO gets multiple audiences with the city, city manager, and economic development council, the people of the Valley are left with the only option of a three-minute comment at city meetings—comments to which the mayor, commissioners, and city manager do not respond to due to the rules that govern the city meetings. Moreover, while the city commission and EDC meetings are streamed and archived, our public comments are neither streamed, archived, or recorded in the minutes.

Essentially, the community is rendered invisible and unimportant.

An elder of San Juan attended one of our early meetings at the San Juan Memorial Library and not only painfully recounted the horrors of Mayfield but argued that the hotel, in fact, should be torn down because it is a reminder of all the pain the community has suffered. For sure, this caused many to rethink the preservation of the hotel. However, overwhelmingly, our members feel that erasing history does not ease the pain. In fact, it exasperates the inability of that wound to heal. The preservation of the San Juan Hotel is not just a call to ensure the preservation of a historic building for architecture’s sake but also to not erase a critical part of Río Grande Valley History.

Tee Bermea, a San Juan resident and owner of Rock N Thrift in San Juan, argued at an ERO open house regarding the downtown revitalization plan that we should not erase history but rather ensure that we learn from it by preserving historical buildings as done in other cities like San Antonio. We call not only for the preservation of the hotel structure but also for it to become a site of consciousness and reconciliation. We need to ensure that people in the Valley and beyond gain awareness of this history and that the community has an opportunity to reconcile the historical trauma inflicted upon them.

The San Juan Hotel not only played a pivotal role in the colonization and establishment of San Juan, but the hotel is also a site of great pain. While in the 1980s, the hotel saw a revival under then owners, the Sigels, and brought great joy to many in San Juan, we cannot forget its role in reinforcing the racial hierarchy that goes hand in hand with colonization through state-sanctioned violence. We cannot allow ourselves to be complicit in the erasure of that history, but rather, we must ensure that history is remembered, taught, and reconciled.

The best way to do that is by preserving the hotel.

How Can You Help Save the San Juan Hotel?

You can help by signing the Save the San Juan Hotel petition, following us on Facebook and Instagram, and sharing your opinions at City of San Juan commission meetings.

Lastly, show up and support our cause. Our next event is FREE and open to the public on April 12, 2025, at The Landmark on Tower, 103 N. Tower Rd. in Alamo, Texas.

For further resources on the history of the Matanza, see “Border Bandits” by Kirby Warnock, “The Injustice Never Leaves You (2018)” by Mónica Muñoz Martínez, Refusing to Forget and “Reverberations of Violence (2021)” edited by Sonia Hernández and John Morán González.